New Drivers of China’s Industrial Growthin Its Late-Stage Industrialization and “New Normal”

Huang Qunhui(黄群慧)*

Institute of Industrial Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China

[Abstract]According to our analysis of variations in China’s industrial growth rate, industrial demand, industrial structure, regional structure and the performance of industrial firms, China’s industrial economy is moving towards a “new normal” of slower growth and structural improvement. This process coincides with the late stage of China’s industrialization, which international experience suggests is often fraught with twists and challenges. Among these challenges, great attention must be paid to overcapacity, industrial restructuring and upgrades, and the “reindustrialization” of developed countries. As China enters the late stage of its industrialization, particularly during the 13th Five-Year Plan period from 2016 to 2020, the promotion of industrial development is of strategic significance for China to successfully complete industrialization and its economy to adapt tothe “new normal”. In the face of these new challenges regarding industrial development, policymakers must strive to increase the dynamism of growth for industrial economy. In this new era, the momentum of industrial growth derives from the integration of the supply impetus of industrialization and the pull of demand caused by urbanization, while the comprehensive deepening of reform provides the key source of momentum.

[Key words]“new normal”, late stage of industrialization, development consensus, innovation-driven

JELClassification: L60, E37, O14

As China enters the late stage of industrialization after decades of rapid economic growth, the Chinese economy is transitioning towards a “new normal” of medium-rapid growth. In 2013, China’s economic structure experienced a transition of historic significance when the share of value-added of the tertiary industry in GDP exceeded that of the secondary industry for the first time. Against the backdrop of such a transition, it is significant to identify the potential challenges facing China’s future economic growth and the new drivers of industrial development.

1. “New Normal” for the Industrial Economy

As a key driver of economic growth, industry as a whole has begun to demonstrate trends towards slowdown and structural optimization in recent years, and the industrial economy has shown signs of moving towards a “new normal”.

1.1China’s Industrial GrowthSlows yet Tends towards Stabilization

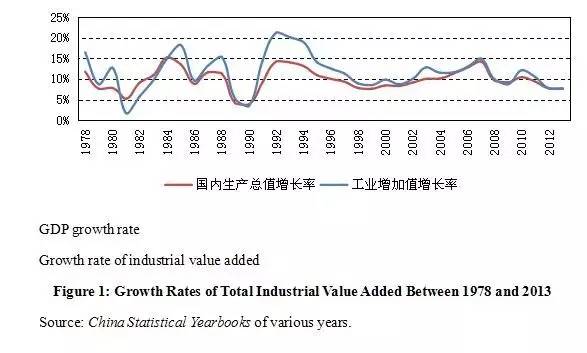

China’s industrial growth since reform and opening-up in 1978 can be roughly divided into the following four cycles (as shown in Figure 1). The first cycle is between 1978 and 1985: the growth of total industrial value added reached 16.4% in 1978, peaked in 1985 at 18.2% and bottomed in 1981 at 1.7%; the second cycle is between 1985 and 1992: the growth of total industrial value bottomed in 1990 at 3.4% and peaked in 1992 at 21.2%; the third cycle is between 1992 and 2007: the growth of total industrial value added bottomed in 1999 at 8.5% and reached 14.9% in 2007. Presently, China has been engaged in a new cycle since 2007. In general, the first two cycles are characterized by greater fluctuation. In the current cycle, overall growth began to decline to a diminishing extent while the industrial economy is stabilizing.

1.2Growth of Industrial Investment Slowed yetInvestment Structure Improved

After2011, the growth of industrial investment in China slowed at a faster pace than did the growth of social fixed asset investment. In 2011, 2012 and 2013, social fixed asset investment grew by 23.8%, 20.6% and 19.6%respectively, while industrial investment growth grew by 26.9%, 20% and 17.8% during the time period. In 2011, the growth of industrial investment outpaced that of social fixed asset investment by 3.1 percentage points, while in 2013 this gap narrowed to 1.8 percentage points. After2014, manufacturing investment growth further slowed to historic lows against a backdrop of sluggish demand at home and abroad. Yet flagging investment tends to lead to optimization in investment structure. In 2013, manufacturing investment increased by 18.5% on a year-on-year basis, down 0.1 percentage points over 2012, while investment in the mining sector grew by 10.9%, down 1.1 percentage points from 2012. This helps to enhance the processing-based industrial structure. For the manufacturing sector internally, high-tech sectors experienced greater investment growth rates while investment growth declined for traditional manufacturing sectors. In the context of overall industrial investment slowdown, investment in the upgrade of industrial technology maintained rapid growth. In the first six months of 2014, investment in technology upgrades increased by 18%, an increase beyond the growth rates of industrial and manufacturing investment by 3.8 and 3.2 percentage points respectively. Technology investment is highly important to enhancing corporate core Ramp;D capacity and promoting energy and water efficiency.

1.3 Consumer Demand Declines Steadily While Consumption Structure Upgrade Begins to Accelerate

In 2013, China’s total retail sales of social consumer goods reached 23.8709 trillion yuan, up 13.1% over the previous year. After removing the price factor, the actual growth is 11.5%, down 0.6 percentage points over the previous year. Between 2006 and 2012, China’s annual gross retail sales of social consumer goods increased by 13.7%, 16.8%, 21.6%, 16.5%, 14.8%, 11.6% and 12.1% respectively. 2013 recorded the lowest growth rate since 2006. In 2014, growth in the retail sales of social consumer goods further slowed. In the second quarter of 2014, real year-on-year growth in the grossretail sales of consumer goods fell to 10.8%. This implies that growth in consumer demand hadgradually decreased with no obvious signs that this decline wouldabate. Yet there was good news in the form of the upgrade of the consumption structure. This is first reflected in the rapid growth of rural consumption, which reached 14.6% in 2013 compared to the 12.9% growth of urban retail sales of consumer goods. Second, since 2006, growth of total retail sales of social consumer goods in the west of China has outpaced that of the eastern region, resulting in narrowing regional consumption gaps. Third, the modes of consumption have diversified. New consumer sectors such as information consumption grew rapidly, becoming new growth drivers of industrial economy. In 2013, China’s information consumption reached an overall scale of 2.2 trillion yuan, up 28% over 2012. In the first five months of 2014, China’s information consumption reached 1.38 trillion yuan, up 19.8% year-on-year.

1.4 Industrial Export Growth Remained Sluggish yetTrade Structure Optimized

In the depth of the global financial crisis of 2008, real growth as measured by the export delivery value of industrial goods plunged. Despite rebounds and swings, growth in the export of industrial finished goods stayed at a relatively low level. In 2012 and 2013, China’s exports increased by 7.9%. In the first quarter of 2014, the total export of industrial finished goods declined by 4.7%. In the second quarter of the year, the total export of industrial finished goods increased by 6.2%. Despite the slow growth in exports, China already became the largest trading nation in the world in 2013. Before 2013, China was already the largest goods exporting country in the world. The key to “new normal” of China’s industrial economy is the optimization of China’s industrial trade structure. Remarkable changes have taken place in China’s trade modes and structure. First, in 2013, the export of China’s electromechanical products and high-tech products grew by 7.3% and 9.8% respectively over 2012, much higher thanthe growth rate of 5% on all industrial exports. Second, the share of exports from processing trade continuously declined. In 1999, this share reached 56.9%. After the turn of the 21stcentury, the share of exports from processing trade continuously declined, down to 38.9% in 2013. Third, trade entities increasingly diversified, and export competitiveness of domesticfirms strengthened. In 2005, the share of exports from foreign-funded firms stood at 58.3%, a figure which fell to 47.3% in 2013. Moreover, export growth in China’s central and western regions accelerated, and import/export markets diversified. Open economic reform deepened. All these indicate a tendency towards trade structure optimization.

1.5 The Service Sector Overtook the Production Industry in Share of GDP

It was a significant event when the service sector’s value added contribution to China’s GDP overtook that of the industrial sector. In the first half of 2014, the value added for the service sector showed year-on-year growth of 8%, which is above the growth rate of 7.4% for secondary industry. The share of contribution of the service sector to GDP continued to rise, reaching 46.6%. As for the internal structure of the production industry, a highly processing-based tendency emerged, and technology-intensive industries and strategic emerging industries developed rapidly. Among the raw materials, equipment manufacturing and consumer goods industries, equipment manufacturing recorded the highest growth. Over recent years, the value added of high-tech industries has been growing faster than the average growth of industrial value added. Development is especially rapid for industries and sectors such as energy conservation, environmental protection, innovative information technology, biomedicine and new energy vehicles. In the first six months of 2014, the value added within the high-tech manufacturing sector rose by 12.4%, which is 3.6 percentage points above overall industrial growth. Of the ten sectors with the slowest growth rates in cumulative value added, most are energy- and resource-intensive.

1.6 Industrial Structure acrossEastern, Central and Western RegionsTends towards Balancing, with Eastern Region’sIndustry Showing Early Signs of Stabilization

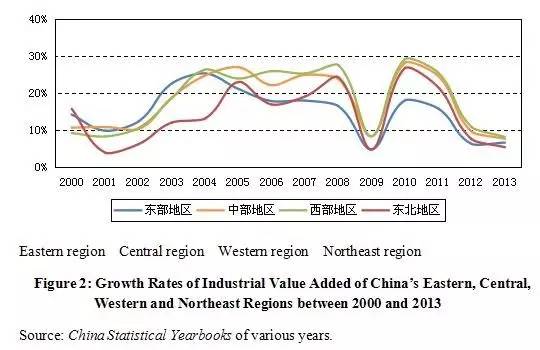

Disparities in economic development among China’s eastern, central and western regions have gradually narrowed over time. As shown in Figure 2, after2005, the growth of industrial value added hadbeen generally slower in China’s eastern region than in its western region, and industrial growth wasthe highest for the central and western regions. In 2008 and 2010, growth of industrial value added in the western region outpaced that of the eastern region by 11.1 and 11.2 percentage pointsrespectively. Despite an overall decline in the industrial growth rates of various regions after 2010, industrial growth in China’s western region still outpaced that of the eastern region by 9.7, 4.8 and 1.6 percentage points in 2011, 2012 and 2013, respectively. In terms of industrial structure, the central and western regions have always maintained an advantage in energy industrial goods such as raw coal, natural gas and electric power. High-tech products such as microcomputers and integrated circuitry also registered remarkable performance in recent years, which indicates the continuous upgrade of industrial structure in China’s central and western regions; despite the absolute advantage of the eastern region in the manufacturing capacity of integrated circuits, TVs, microcomputers and steel, such an advantage was declining relatively. Fortunately, industrial development in China’s eastern region already showeda tendency toward stabilization;in 2013, the industrial value added of China’s eastern region increased by 0.3 percentage points over 2012, while industrial growth rates for China’s central and western regions and northeast all declined.

1.7 Industrial Firms Became Less Profitable but More Innovative

With the slowdown of industrial growth which began in 2011, overall corporate profitability declined. China’s industrial innovation capacity increased in recent years, reflected in swelling Ramp;D spending. In 2012, the internal Ramp;D spending of large industrial firms reached 720.06 billion yuan, up 20.1% over 2011; Ramp;D intensity reached 0.77, which increased from a base of 0.71 in 2011 and 0.69 in 2010; in terms of output, the number of patents registered by domestic firms reached 78,000, which is 2.2 times the amount in 2010. More importantly, major breakthroughs weremade regarding advanced and core technologies in key areas. In 2013, the petrochemical sector made breakthroughs in coal gasification equipment, dying material production, shale gas and coal chemicals; looking at the pharmaceutical industry, the number of Category-1.1 new drug clinical applications is growing, reaching 13% of the total; the information industry made such breakthroughs as 55-nanometerphase-change storage technology and high-performance image sensor chips (Research Academy of Industry and Information Technology, 2014). Against a backdrop of industrial slowdown, the fact that industrial firms maintained stable profitability while increasing innovation indicates a transition in the growth pattern from quantitative expansion to qualitative growth and from low-cost strategies to differentiated strategies. Firms werestriving to enhance their core competencies through technological innovation and adaptation to the medium growth rate inthe “new normal.”

2. Embracing the New Challenges of the Late Stage of Industrialization

Since 1978, China has successfully expedited its industrialization process. According to our long-term tracing and evaluation (Chen Jiagui, Huang Huiqun et al., 2012), the composite index of China’s industrialization level already reached 66 in 2010, which means that China entered the late stage of industrialization in 2010. As suggested by the experience of various countries, an important feature of economic development during the late stage of industrialization is rapid growth supported by high investment,and heavy and chemical industries will become unsustainable,and growth rates will fall. This implies that China’s economic development is indeed facing a major transition from middle to late stage of industrialization, which coincides with the “new normal.” According to the 18th CPC National Congress, China should initially achieve industrialization by 2020, which means that such a transition is urgent. As shown by the history of industrialization, late-moving countries may achieve rapid economic development and catch-up by learning from and imitating the systems, technologies and means of production of advanced countries in the process of their industrialization. Yet in reality, the industrialization process of late-moving countries is often fraught with twists and turns, as well as challenges and crises such as the “middle income trap” in the middle stage of industrialization. Therefore, very few countries actually complete industrialization through successful “catch-up”; generally only Japan and the Four Asian Tigers are described as having done so successfully by economists. Hence, as China enters the late stage of industrialization, great challenges are inevitable, including innovation, industrial transition and upgrade, an ageing population, limited natural resources, environmental problems, regional disparities and income distribution. That is to say, the path towards “new normal” is twisted and challenging. Our view is that, among the numerous challenges, great attention should be given to excess capacity, industrial restructuring and upgrade,and the “re-industrialization” of advanced economies. The first two factors are endogenous variables for China’s industrialization process. They are problems and tasks to be addressed in the course of China’s own development. Yet the “re-industrialization” of advanced economies is an exogenous variable of China’s industrialization and constitutes a major challenge.

2.1Overcapacity

Overcapacity is regarded as a common problem in a market economy, and it became a serious problem in China at the end of the 20thcentury and around 2005. In this sense, overcapacity is not a unique problem facing China’s late stage industrialization. However, since 2011, the current round of overcapacity has presented unusual challenges to China’s economy.

First, the current round of overcapacity involves more sectors and is more severe. Around 2005, China’s excess capacity mainly existed in traditional sectors such as iron, steel, cement, non-ferrous metal, coal chemicals and plate glass. The current round of overcapacity, however, has expanded to such sectors as shipbuilding, automobiles, machinery and electrolytic aluminum;itis particularly serious in such sectors as iron, steel, electrolytic aluminum, cement, plate glass and shipbuilding. Moreover, overcapacity occurred in strategic emerging industries as well, including photovoltaics, multi-crystalline silicon and wind power equipment which represent the future directions of industrial development. Given the lack of official capacity utilization statistics, we cannot accurately measure the degree of China’s overcapacity. Yet producer price index (PPI) experienced negative growth for 33 consecutive months between March 2012 and December 2014. Although many factors are behind declining PPI, negative growth of PPI for 33 months in a row largely explains China’s serious overcapacity, high inventory and sluggish real economy.

Second, since China is currently in the late stage of industrialization, it becomes nearly impossible to resolve overcapacity by waiting for a period of rapid growth following economic recovery. In the late stage of industrialization, China has already become a major industrial economy with more than 200 types of industrial goods ranking first in the world in terms of output. The next priority is to strengthen the quality and competitiveness of industry. In this process, relative overcapacity has evolved to absolute overcapacity. That is to say, although previous cyclical overcapacity could be gradually consumed by long-term demand, annual demand of many sectors already peaked in the late stage of industrialization, and the peak can no longer be consumed by long-term demand.

Third, current overcapacity reflects an urgent need for a transition in growth patterns and low-cost industrialization strategy, as well as a problem of incomplete institutional reform. There are profound and complex reasons why the seemingly simple problem of overcapacity is likely to beleaguer China’s economic development in the long run. As opposed to sophisticated market economies, China’s overcapacity derives not only from cyclical economic fluctuations as a result of changes in market supply and demand but also from major shifts in the stage of economic development. Compared with the previous two rounds of excess capacity, current overcapacity has made institutional reform and development pattern transition even more urgent. If the pattern of economic development and excess intervention of local governments cannot be changed, then not only will existing overcapacity be difficult to consume, but new overcapacity will continue to emerge.

2.2Industrial Restructuring andUpgrade

Promoting the strategic adjustment of China’s economic structure has always been a top priority for China’s economic policy and macroeconomic management. Among China’s various structural problems, the improvement of demand and industrial structures and the promotion of balanced regional development are considered to be major structural issues confronting China. Demand structure problems are reflected in the structural imbalances of insufficient domestic demand and sluggish consumption. Problems of industrial structure include weak agriculture, low-quality and uncompetitive industry and a backwards service sector, particularly in modern producer services. As for regional structures, problems include the uneven development inurbanization and between central and western regions and great disparities in living conditions and public services between rural and urban areas and between geographic regions. Among these challenges, optimizing industrial structures and promoting industrial transition and upgrade are considered top priorities for China’s economic restructuring. Industrial restructuring and upgrade refer to an evolution from the dominance of primary industry to secondary and tertiary industries and from the dominance of labor-intensive industries to capital-, technology-and knowledge-intensive industries. In fact, industrialization itself is a process of transformation where agriculture is replaced by industry as the dominant sector of the economy, accompanied by a structural transition and rising per capita income levels. In the late stage of industrialization, the upgrade of industrial structure is embodied in the decline of the share of secondary industry and the rise of the share of tertiary industry, as well as the declining share of labor- and capital-intensive industries and the rise of technology-intensive industries.

In the late stage of industrialization, industrial restructuring and upgrade constitutes a major challenge because the task cannot be accomplished overnight. In the early and middle stages of industrialization, China transformed from an agricultural economy to an industrial power mainly based on a “factor-driven strategy.” In the late stage of industrialization, China needs to adopt an “innovation-driven strategy” in order to evolve into a strong and competitive country of industry and services. The “factor-driven strategy” entails the mass input of such factors as investment, workforce, resources and the environment at low costs to drive economic growth, while an “innovation-driven strategy” underscores sustainable economic development through technological and institutional innovation. Over the past three decades, the mass relocation of the rural surplus workforce has significantly enhanced the labor participation rate inindustrial sectors, which is far above that inthe agricultural sector, and greatly increased the overall labor participation rate. In this manner, factor input drove economic growth. As China enters into the late stage of industrialization, the labor participation rate will decline, demographic dividends will diminish and more labor will enter into the service sector, where the labor participation rate is below that inindustry. Thus, the overall labor participation rate will decline, giving rise to “economic structural deceleration” and “industrial efficiency imbalance” (Zhang Ping et al., 2014). Therefore, the key to the enhancement of labor efficiency lies in the innovation of technology and business models, which is known as innovation-driven growth. While China’s industrial development is below advanced international levels, China’s service sector lags even further behind. In the late stage of industrialization when the share of the service sector grows, not only will this disparity slow down the improvement of China’s overall efficiency, but, more importantly, the innovation of the service sector will face greater challenges compared with industrial innovation. This means that China still has a long way to go before innovation becomes a real driver of growth.

2.3“Re-industrialization” of DevelopedCountries

After China enteredinto the late stage of industrialization, its own industrialization process is superimposed with the “reindustrialization” of developed countries, which brings about uncertainties to China’s industrialization process. Developed countries embraced the “reindustrialization” strategy against a backdrop of declining competitiveness as a result of an overblown virtual economy, flagging real economy and hollowing domestic industrial structure. The “reindustrialization” strategy is not simply another round of industrialization as the name suggests. Its key message is not to restore and expand traditional manufacturing by moving overseas factories back home. Instead, the “reindustrialization” strategy aims to promote the breakthrough and application of advanced manufacturing technologies of artificial intelligence, digital manufacturing, 3D printing and industrial robotics through the long-term accumulation and advantage of information, communication and new material technologies. After the eruption of the global financial crisis, the United States adopted the National Strategic Plan for Advanced Manufacturing, Germany developed its Industry 4.0 initiative and Europe embraced Factories of the Future (FoF), all of which aim to reshape their manufacturing competitiveness through advanced technologies.

The “reindustrialization” of developed countries, with the “Third Industrial Revolution”as its core, is in direct competition with China’s industrialization. This may present shocks and challenges to China’s industrialization process in the following two areas (Huang Qunhui, He Jun, 2013): For one, it further weakens China’s factor cost advantage and forces China to shift its low-cost strategy of industrialization. By facilitating the application of advanced manufacturing technologies, the “Third Industrial Revolution” will surely increase labor productivity and reduce the share of labor in aggregate industrial input. As a result, China’s comparative cost advantage may weaken at an accelerated pace. At the same time, it may inhibit China’s industrial upgrade and restructuring. Modern technologies strengthened the value creation capacity of the manufacturing process, making the manufacturing process as important as Ramp;D and marketing. The “smile curve” that describes the value creation capacity of various processes is likely to become a “silent curve” or even a “sad curve.” Advanced industrial countries may not only possess new industrial vantage points by developing industrial robotics, high-end CNC machine tools and flexible manufacturing systems, but they may greatly enhance the productivity of traditional industries by employing modern manufacturing technologies and systems. Manufacturing activities that moved out of developed countries in search of lower costs are thus likely to move back to developed countries, causing the gravity of manufacturing to shift in favor of developed countries once again. The catch-up path for late-moving countries as predicted in the traditional “flying geese theory” is likely to become blocked.

3. Enhancing the New Momentum of China’s Industrial Growth

In the face of various challenges in the late stage of industrialization, China’s ability to enter into the “new normal” of industrial economy depends on two aspects: first, although industrial growth will slow, it must not slide below an acceptable bottom line to still be able to maintain medium-rapid growth; second, industrial structure must optimize in terms of sophistication and soundness. With weakening industrial growth in the late stage of industrialization, the key to ensuring industrial growth and structural optimization lies in whether industrial growth mechanisms can be transformed to enhance the momentum of growth. Only with new drivers of growth will the economy maintain steady operation in the “new normal”, overcome potential crises in the late stage of industrialization and complete industrialization. In the late stage of industrialization, the momentum of industrial growth can be ascribed to the following major aspects: first, the impetus of supply arising from technological progress and industrial upgrade in the evolution of industrialization; second, increased demand generated by urban development and urbanization. Integrated with China’s industrialization and urbanization, information technologywill be a key driver of industrial growth in the late stage of industrialization. In the face of sluggish labor and capital factors, a more fundamental impetus is innovation, which is the real intent of “innovation-driven strategy.” Such innovation includes not only technical innovation in the common sense but institutional innovation in the sense of meaningful reform. Considering that China’s technical innovation is largely restrained by institutional mechanisms, the source of China’s industrial growth in the late stage of industrialization is more a reflection of institutional innovation.

References:

(1) Chen,Jiagui, Qunhui Huang, Tie Lyu, and Xiaohua Li. 2012.Report of China's Industrialization Process (1995-2010).Beijing: Social Sciences Literature Press.

(2) Fang,Lingsheng. 2013. “Technologies That Will Disrupt Our World.”Wen Wei Po, July.

(3) Huang,Qunhui, and Jun He. 2012. “The Third Industrial Revolution” and Strategic Adjustment of China’s Industrial Development: Perspective of Shifting Technical and Economic Paradigms.”Journal of China’s Industrial Economy, (1).

(4) Huang,Taiyan. 2014. “The Third Transition of China’s Economic Momentum.”Economic Perspectives, (2): 4-14

(5) Liu,Shijin. 2014. Development of the New Normal of Growth in Reform. Beijing: CITIC press.

(7) Research Academy of Industry and Information Technology. 2014. Report of China’s Industrial Development 2014. Beijing: Post and Telecommunication Press.

Zhang,Ping. 2014.China Economic Growth Report(2013-2014). Beijing: Social Sciences Literature Press.